Whereas the Bronze Age in north Devon is normally characterised by many burial mounds and few settlements, this is completely reversed in the Iron Age, where there are many ramparted enclosures (commonly called hillforts), but not a single known burial (1). The term hillfort is actually misleading, since only some of the enclosures were defensible. Most were built on the side of a hill, rather than the crown, and were vulnerable to attack; these are now called hill-slope enclosures.

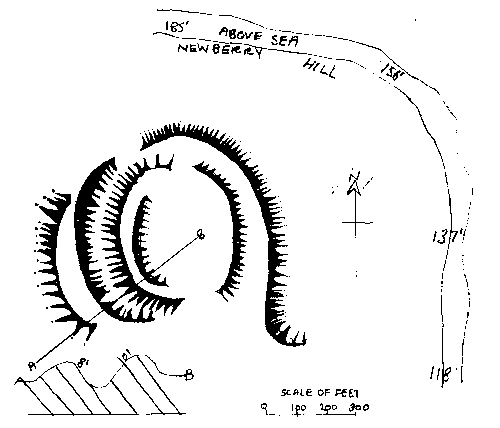

The classic defensible hillfort, where the top of a hill is completely

surrounded by ramparts, is represented locally by Newberry Castle at Combe

Martin (left); Knowle Castle

near Braunton and Roborough Castle at Burridge near Barnstaple. A hill-slope

enclosure at Smythapark may have been made defensible by the addition of

outworks. But the most impressive hillfort in the region is surely that upon Hillsborough

at Hele, where two massive ramparts run across

the headland, enclosing a large area on top. This type of hillfort is often

called a promontory fort, and Hillsborough is the only one locally (the nearest

are at Wind Hill, Countisbury and at Embury

Beacon near Hartland). Hill-slope enclosures are much more common than hillforts and it is assumed, though not proven, that they were subordinate in

hierarchy. The most impressive hill-slope enclosure in north Devon is at Clovelly Dykes (2).

The classic defensible hillfort, where the top of a hill is completely

surrounded by ramparts, is represented locally by Newberry Castle at Combe

Martin (left); Knowle Castle

near Braunton and Roborough Castle at Burridge near Barnstaple. A hill-slope

enclosure at Smythapark may have been made defensible by the addition of

outworks. But the most impressive hillfort in the region is surely that upon Hillsborough

at Hele, where two massive ramparts run across

the headland, enclosing a large area on top. This type of hillfort is often

called a promontory fort, and Hillsborough is the only one locally (the nearest

are at Wind Hill, Countisbury and at Embury

Beacon near Hartland). Hill-slope enclosures are much more common than hillforts and it is assumed, though not proven, that they were subordinate in

hierarchy. The most impressive hill-slope enclosure in north Devon is at Clovelly Dykes (2).

The hill-slope enclosures are similar to the Cornish round, a circular bank and ditch enclosing ½ to 2 acres. The earliest of these date from the 4th century BC and it has been estimated that there may have been 3,500 of them in Cornwall in the late Iron Age, underlying many present day settlements. But the enclosures in Greater Exmoor tend to be more oval in shape and show far less continuity with later settlement. It is usually assumed that most are from the Iron Age, Roman and even post-Roman periods (3). It has been suggested that the more complicated enclosures, i.e. those with multiple ramparts (multivallate), or with overlapping or inturned entrances, are later than the simpler forms, but there is no proof of this (4).

Until recently, the only enclosures in north Devon to have been excavated are Embury Beacon near Hartland (found to contain some wooden structures and fragments of Glastonbury Ware, a kind of pottery common from the 3rd century BC onwards) and Milber Down near Tiverton (found to have been abandoned a short time before the Roman invasion). Consequently it was usually assumed that enclosures in north Devon date from around c300 BC to c50 AD. However, recent excavations at Holworthy enclosure show that it was occupied in the Bronze Age and abandoned by 1000BC, before the Iron Age even began! It is very likely that other local enclosures will be found to date from the Bronze Age, or even earlier (5).

This drawing (right) shows the known hillforts (red) and hill-slope enclosures (yellow) around Ilfracombe. The higher density of hill-slope enclosures on the moors is probably because elsewhere they have been destroyed by later settlements and farming. The main hillforts seem to form a protective ring around the area. The hillforts at Hillsborough and Newberry suggest that the north coast was occupied and it is likely that there was a coastal 'ridgeway' (below left), passing by the hillforts and joining the ends of the branch ridgeways to Ilfracombe, Widmouth Hill, Berrynarbor and Combe Martin (6).

The hillforts were built by a loose confederation of Celtic tribes, collectively known as the Dumnonii (the root of the word Devon), meaning 'the people of the land'. The south west is known to have traded with the Mediterranean before the Roman invasion, and whilst there is archaeological evidence of early trading in south Devon, north Devon was always thought to have been relatively economically backward (7). However, recent finds in and around Brayford have shown that there was very considerable Roman and pre-Roman metal working in the region. It is likely that the Iron Age people also knew about the silver deposits in and around Combe Martin - perhaps the hillforts at Newberry and Hillsborough protected the local ore, or provided a status symbol of the local tribe's mining wealth (8).

< Bronze Age Hillsborough hillfort >

(1) End of barrows

"After about 1000 BC much of the traditional burial record disappears. Only the flat cemeteries continued for a period, in some cases perhaps as late as 600 BC, when these too cease to be used. Coincident with this decline in burial sites is an increase in the amount of fine metalwork found in rivers, lakes and bogs. Colin Burgess has suggested that wet places became the focus of a new water cult in Britain around the turn of the first millennium" (Davrill 1990 p119-120)

"[in the South-West] inhumation graves and stone lined cists were common. Burials were usually crouched, and grave goods poor, at best simply a few personal ornaments such as pins, brooches or a bracelet" (Davrill 1990 p 158)

"By about 1200BC the practice of burial in mounds had much declined, but a burnt burial was exposed in late 1930s in the cliff face south of Barricane beach and 6 yards south-east of the southern concrete platform, and in view of the likelihood of the outbreak of war, a hurried excavation was carried out by H & E Taylor in Sept. 1938. A pit was discovered, lined with clay, in which were black ash, charcoal and calcined human bone, and it is thought that this was a cremation, although the site was too small to burn a complete body. The bones were adult, included skull, teeth, vertebrae, ribs, pelvis and upper and lower limbs were represented. Also in the pit were three burnt flint pebbles, maybe sling stones, and some black deposit which may have been animal matter. There were no dateable objects, but it was thought likely to be early middle Bronze Age, perhaps 1,000 BC (see Taylor 1948). A similar burnt burial is recorded at Croyde." (Reed 1997 p4)

(2) Hillforts & Hill-slope enclosures

Many of the sites below, and the location of the local hillforts in the drawing above, are from 'Hillforts and enclosures in North Devon' (Griffith,F & Quinnell, H) Settlement c2500 BC to AD 600, in Kain, R & Ravenhill, W 1999 p 66).

Berry Cross enclosure

Hill-slope enclosure - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66 SS570435?

Burridge

Hillfort - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66; Grinsell 1970 & 1970a SS569352

Burridge hillfort is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, No. 419, at SS569353

Palmer card index in Ilfracombe Museum "Burridge, Roborough, old track to southern platform"

"Roborough Castle is the most westerly and also the largest of this type of fort. It lies on the crest of Burridge (burh-hrycg) in a commanding position overlooking several miles of the Taw estuary with Pilton and Barnstaple near the head of deep-water navigation. From the site of the fort at about 470’ the sides of the ridge fall very steeply on the north and south nearly to sea level in the valleys of two tributaries of the Taw, Braddiford Water and the River Yeo. The spur of the ridge descends gently westward for about 250 yds before falling steeply to Braddiford Water. Eastward the ridge falls very slightly for about 200 yds and then rises equally gently to its highest point, 480’. Thereafter it undulates between about 420 and 20’ before joining a complex of hills at Shirwell, a mile or so away. The main part of the fort measures about 400’ each way inside the ramparts, being a few feet wider at the east end than at the west. It is an approximate quadrilateral with a considerable salient at the south-east corner. The single entrance, much damaged but apparently of the overlapping type, is a few feet south of the middle of the eastern side. The rampart is rather more massive than is usual in the area, though probably not significantly so. On the east and west sides it has been incorporated into modern hedge banks and thus preserved, although the ditch has been largely filled in except near the south east corner. The north and south ramparts have been eroded so as to appear as scarps, and the ditches here have been completely filled in. So far Roborough Castle appears a very ordinary univallate enclosure much like, for instance, Mockham Down (ss667358) in the parish of Charles, six miles away to the east. The interesting feature of Roborough Castle is that about 485 yds east of its east rampart is a transverse bank and ditch which are fairly obviously an outlying reinforcement of the main work. This outwork is ascertain ably about 470’ long, its north end terminating where the face of the ridge becomes so steep that fortification becomes unnecessary. To the south the earthwork apparently ends at the modern lane (the pre-turnpike way from Pilton to Shirwell). This point is a few feet south of the crest of the ridge. It is probable but not certain that this rampart and ditch continued to the south of this lane for perhaps 200’, being embodied in a modern hedge bank. If so, the entrance would have been where the lane now passes, and the alignment of hedge banks north and south of this lane makes it almost certain that the entrance was of the overlapping type which exposes the unshielded right flank to attackers. A possibility, perhaps attributable to the late J F Chanter but not directly traceable to him, that Roborough castle was reoccupied in the Dark Ages and may have been the seat of the kinglet St Selyf and his son St Kebi or St Kea (Trans Dev Assoc LVII p 58) is worth mention but not pursuit. More probable is the suggestion that it may have been the site of King Alfred’s original burh of Pilton, moved after a few years to Barnstaple, just as his hillfort burh of Halwell was transferred to Totnes (Trans dev Assoc LXIII p 357)" (Whybrow 1967 p 3-4)

"Burridge [ss569353] hillfort, with an outwork of south-west type, is situated at 140m on the crest of a steep-sided ridge between the river Yeo and Bradiford water...The enclosure is approximately 100m square with rounded corners and was defended by a substantial rampart and ditch, best preserved in woodland on the west side. On the south the defences have been lowered by ploughing; elsewhere the rampart is incorporated in the hedge banks and the ditch filled in. The entrance is slightly inturned and faces east but is obscured by a hedge bank. Some 400m east along the ridge is a massive cross-bank and ditch 2m high extending between the steep slopes; there was probably an entrance on the line of the present ridge road to Shirwell. It probably defined a large stock enclosure....It has also been suggested that this Iron Age hillfort was reoccupied in the late 9th or 10th century AD by the Saxons as a defence against the Danes and is to be identified with the site of Pilton, listed in the Burghal Hidage, before the focus of Saxon settlement was transferred to Barnstaple." (Fox 1996 p 49)

Dean Cross

Hill-slope enclosure - SS62544485 (Riley & Wilson-North 2001 p 180)

Hillsborough

Hillfort - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66; Grinsell 1970 SS532477; Whybrow 1967 SS533479

Hillsborough promontory fort, Ilfracombe, is a Scheduled Ancient Monument No 414, SS533478

"A really fine example of the Cornish type of cliff castle, the only one known on greater Exmoor unless the great earthworks at Wind Hill (Countisbury) be included in the category" (Grinsell 1970, quoted in Lampugh 1984 p 3)

See next section on Hillsborough hillfort.

Hore Down/little Stowford

enclosure (Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p66) SS533435? NOT Scheduled

Kentisbury Down

Hill-slope enclosure - SS64274330 Riley & Wilson-North 2001 p 180; Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66; SS643433 Grinsell 1970; spindle whorls SS640435 from hillslope enclosure Grinsell 1970

Kentisbury, Scheduled Ancient Monument No. 95 Kentisbury round barrows and camp SS643433 SS643434 SS643435 SS642434

"On the south east slope of Kentisbury Down, just west of Blackmoor Gate, is a small univallate hill-slope enclosure, the north-west sector has been levelled by cultivation." (Grinsell 1970 p 82)

Knowle castle

Hillfort - Kain & Ravehill 1999 p 66

Knowle Castle, Scheduled Ancient Monument No. 513 SS489383

M G Palmer, card index at Ilfracombe Museum "Knowle 400’OD May be ancient hillfort with some Norman stonework"

"Knowle castle is partly a folly of the c19th but may be on an Iron Age forerunner." (Grinsell 1970 p 81)

Lee Wood enclosure

enclosure - Whitehall (Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p66) SS539375? NOT Scheduled Grinsell 1970 SS537374

"The earthwork in Lee Wood (Marwood), not yet on OS maps, is a hill-slope fort about 70 paces diameter on the western spur of the hill north of Lee House, in the valley west of which flows the Knowl water. Almost 4 miles east of it is the castle at Plaistow Barton, a small univallate hill-spur earthwork of which the north-western sector has been largely levelled by ploughing. The entrance is on the north-east, where the northern rampart is inturned. There are traces of outer ditch." (Grinsell 1970 p 82)

Mockham Down

Hillfort - SS667358 Grinsell 1970

"On the summit of Mockham Down [ss667358] at the 300m contour on level ground, there are the conspicuous remains of an oval enclosure. The site is well defended on the north and east by the steep slopes to a tributary of the River Bray. The hillfort (some 150m in diameter) was defended by a single rampart 2m high and a ditch. The north side, where the original entrance was placed, has been badly damaged by a deep stone quarry" (Fox 1996 p 43)

North Hill Cleave

Hill-slope enclosure - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66

Lynton Cross SS548438 is a Scheduled Ancient Monument No. 998

Newberry Hillfort

Hillfort - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66; Castle camp Grinsell 1970 SS572471, Not Scheduled

"On the summit [of Newberry Hill] are the remains of an earthwork known locally as the Castle. The best way to get at this 'camp' is through a gate a little further up the road, where it may be attacked in flank. Arrived on the summit, it will be found that the earthwork is, as usual, circular, and, therefore, in all probability of Celtic origin. It is some 300' in circumference, with a bank about 10' high on the outside, where it is protected by a ditch, though the height measured from within does not exceed 4'. To the east the hill is so precipitous that neither bank nor ditch was necessary. The entrance is to the south-west." (Page 1895 p 69-70)

Tracing of a drawing of Newberry Castle shown above is (Ilfracombe Museum, Berrynarbor folder) said to be from 1906 The Victorian History of the Counties of England, Vol I Devonshire Chapter 1, Ancient earthworks p 602 and has the caption "The Castle is an irregular camp on a height over looking the harbour of Sandy Bay in Combe Martin Bay on the north coast. The ground slopes down towards the south, on which side was the entrance, the west of which is defended by a strong Curved agger with an escarpment of 10 ft. and a counterscarp'8 ft, in height. The highest part at the north is covered with a dense copse; but the natural hill was apparently considered impregnable; the east side also depends on nature for defence. A small stream flows at its eastern base."

"CAMP Newberry Hill near Combe Martin. Situate in Berrynarbor parish. About 350 ft OD between Sandy Bay and Combe Martin. The northern face of the hill is protected by the steep fall to the sea. The E, S and western faces are banked and ditched. There are two entrances, one north east and the other SSW. There is a mound towards the northern side. Note: A typical hill-fort with well marked entrances, ditches and banks with an encircling bank beyond the fort proper. On the plain between the outer and inner bank is an oval mound towards the SE corner" (M G Palmer, Card index in Standing Stones folder, Ilfracombe Museum)

"The hill slope earthwork known as Combe Martin castle, on the north-eastern spur of the hill overlooking Sandy Bay, west of the town, is difficult of access at the time of writing. Mervyn G Palmer reported a few years ago that the south and west sides are strongly defended by ramparts, ditch and counterscarp. It is uncertain whether gaps at the north and south are original or later" (Grinsell 1970 p 81)

Smythapark hillfort

Hill-slope enclosure - Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66; Grinsell 1970 SS636385

Smythapark hillfort, Loxhore , Scheduled Ancient Monument No. 412 SS637384

"The complex of earthworks at Smythapark consists of an almost circular enclosure and two outer cross banks at the end of a broad spur formed by an unnamed tributary of the east Yeo on the north, and of the East Yeo (or Bratton Water) itself on the east and south. Westward the spur merges into the upland which forms the bulk of Loxhore parish. The site is about 4.5 miles N-E of Roborough castle. The most easterly of the Smythapark earthworks is the almost circular ‘round’, a univallate enclosure about 200’ in diameter lying about 660’ above the sea. The river at the foot of the spur is rather more than 200’ lower. The rampart and ditch have been so effectively ploughed as to make measurement difficult. They must, however, have been quite massive, as, although the vertical height of the rampart is only 1.5-2’, the overall width is nearly 60’ and the scarp measurement nearly 30’. The entrance has been obliterated. At distances between 500 and 700’ west and north-west of the west side of the round is a massive rampart and ditch in the shape of an ‘L’ or dogleg which runs across the spur, terminating at each end where the increasing steepness of the valley sides made heavy fortification unnecessary. The south leg of the ‘L’ has been utilised as a modern hedge bank and its height has therefore probably not been much reduced from its original state, though the ditch has been largely filled in. In this south leg there is a well-defined widely inturned entrance, the only example in the western Exmoor area of this type of gateway, although there is a good one in the unfinished fort at Elsworthy Burrows (ST070337) at the eastern end of the Brendon hills in Somerset. The best preserved part of the Smythapark outer rampart is at the junction of the two arms of the dogleg, where the vertical interval from ditch bottom to rampart crest is not less than 12’, in spite of the ditch being almost completely silted. At this point the scarp measurement is 22’ and the overall width of ditch and rampart about 50’ - the outer verge of the silted ditch is ill-defined. The north arm of the dogleg is much ploughed down, the vertical interval being not more than 2’. Here the overall width is 50’ and the scarp 22’. There are remains of an intermediate rampart 200’ west of the circular enclosure and 300’ east of the south end of the south leg of the outer rampart. It runs roughly north and south, but its northern end fades into the ground and becomes indistinguishable. Its length is probably 400-500’. Its south end reaches the steep brow of the spur and here turns outward (west) for a few feet. Near this south end the vertical interval is 3’, the scarp 45’ and the overall width of rampart and ditch 65’; but it seems probable that the wide ditch here may be partly due to natural drainage and erosion. Unlike the other spur-forts which are being considered here, in which the main perimeter enclosure and the outer cross-banks give the impression of having probably been built about the same time as part of a single plan, Smythapark appears to have probably been built in two parts. The earlier part is the ‘round’, originally a family settlement with room for two or three huts and a small herd of livestock. It is perhaps not unreasonable to suggest that a later head of this family was some sort of a local chief or headman, and that, with his followers and kinsmen, he then built the two lines of outer ramparts in order to provide them and their families and livestock with defence when danger threatened. It might be suggested that the area between the two cross banks could then be a camping ground for refugee warriors who would then be close at hand to man the outer rampart. The inner line, so obviously weaker than the outer, confined the livestock to an area where they could not be in the way of the defenders and could not be easily driven off by raiders." (Whybrow 1967 p 4-5)

West Challacombe/Knapp Down

Hill-slope enclosure (Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66) Not Scheduled

Whitestone/Lincombe

Enclosure (Kain & Ravenhill 1999 p 66) Not Scheduled

"CAMP Lower Campscott Lon 4/9/10 Lat 51/11/26 Situate within Ilfracombe boundary, near lower Campscott farm on other (southern) side of the valley where the road runs to Lee. Altitude bout 540ft OD. Unique in our district being cut out of the living rock instead of being banked up. From it can plainly be seen Whitestone Menhir across the valley opposite. Measures 50' from N to s roughly square. there is a low ledge at the N front the floor being some 10 or 12 inches lower than the ground level. There is a drain in the sw corner with water running. The north front projects somewhat like the proscenium of a stage" (M G Palmer, Card index in Standing Stones folder, Ilfracombe Museum)

Holworthy

Enclosure SS68704433 "comprising an ovoid enclosure with an associated linear feature running away from it at a tangent (see p72 The Field Archaeology of Exmoor)" the site is not scheduled and a geophysical survey in June 2002 confirmed the existence of an oval feature with a possible entrance and what appeared to be a ditch (a group of dowsers suggested, without prior knowledge, an entrance in more or less the same location). On 15th July a six day stint opened 3 trenches; across the linear feature (which was thought to be the revetment of a natural ridge), across the edge of the enclosure (which seemed to be a stone bank about 3m thick with no ditch, although an outer post-hole was found) and in the area thought to be the entrance (no clear sign of an entrance but evidence of a stone floor). The only dating evidence were two sherds of medieval pottery from the topsoil and some worked flint beach pebbles, thought to be Mesolithic. Since rampart made of stone, presumably from clearance, no need for a ditch. The medieval sherds suggested medieval ploughing which may explain the linear bank. No date can be suggested for the enclosure. (T Green NDAS Issue 4 Autumn 2002 p5-9)

Holworthy Magnetometry (NDAS Issue 5 Spring 2003 p7):iron-holworthy-enclosureA with caption "Preliminary result of the magnetometry survey conducted by Ross Dean on the Holworthy hillslope enclosure. Overlaid on the plot are the earthworks previously recorded by English Heritage"

Two trenches were excavated in 2003 inside the Holworthy enclosure (SS687443) to cut a small internal rampart feature. Where the trenches met, "a number of small flint flakes and small thumbnail scrapers were found. These were the first evidence we had that might point to a prehistoric date. More was soon to come, however. In the central section of trench 2, the stones lay less densely and plough-soil was initially removed with a mattock. Working in this area, Alistair Miller noticed a soft spot. A pobe with a trowel produced half a dozen fragments of thick, crumbly pottery and subsequent careful trowelling showed that we had the largely intact base of a vessel, the feel and fabric of which suggested prehistoric, specifically Bronze Age. The vessel appeared to have been sheared off by the plough, but fragments had not scattered far.......We are gratified to find that it is in fact the intact base of a vessel now identified by Henrietta Quinnell as Middle Bronze Age Trevisker ware and one of very few found in north Devon or Exmoor." (T Green NDAS Issue 6 Autumn 2003 p 7-9)

The Holworthy pot was a domestic item, not funerary and further excavations have revealed evidence of a 9m diameter round-house within the enclosure. So far it appears that the settlement was abandoned c1000BC. (T Green, personal communication 1/12/2005). There is a photograph of the Holworthy pot in the previous section about the Bronze Age.

Brewers & Mouncey

"Two forts which are always considered together, for no other good reason than that they are only two or three hundred yards apart (though separated by the river Barle) are Mounsey castle [ss885295] and Brewer’s castle [ss884298] . The fact that in modern times they are called by the names of two great Norman families might make one think that they had Norman origins or connections. But there can be little doubt that they belong to the pre-roman Iron Age. But whether they were built or even occupied at the same time is far from certain - the Iron Age lasted for some five centuries. Brewer’s Castle, the more northerly of the two, although on the winding river’s south bank, is a univallate enclosure of no intrinsic interest. Mounsey Castle is a much more impressive fortification, although its layout, now hidden in woodlands, is not at once obvious. Its site is more completely defensible than any other Exmoor hillfort. On three sides the land below its ramparts falls very steeply to the river below. On the fourth side it is defended by a ravine except where a narrow razorback ridge connects it to the wider lands sloping up to Mounsey Hill and Winsford Hill. For most of its circumference Mounsey Castle is univallate, but round part of the east and south sides, where the land is not so steep, there is a second, outer rampart. There are entrances at both the north and south. It seems likely that Mounsey castle, and perhaps also its apparent satellite, Brewer’s Castle, were sited to defend a river crossing; there is a ford as well as a modern bridge below the ramparts. But one feels that Iron Age men would not have worried much about getting their trousers wet if forced to cross higher up or down stream. And so I doubt whether either of these "Castles" was built to defend a river crossing. It seems more likely that the builders and inhabitants selected these spots for the sake of trade. When the river was in spate, travellers might be compelled to wait on one bank or the other for a day or two or three. The river Barle in flood is an awesome sight. The people of Mounsey or Brewer’s would lodge and feed them at a price. The ramparts of the "Castles" were defence against human or animal incursions. All this supposes a frequented road passing near the "castles" and crossing the river, and this road undoubtedly existed. In later times it was called the Old way. For three or four miles southwards of Brewer’s it formed, and still forms, the county boundary, down to the point where it crosses the old Barnstaple-Taunton coach road at Oldways End. But you can, if you will, follow it for mile after mile onward to the south-west, past Chawleigh and away towards Dartmoor. Where this road led to the northward is at present not clear, but it certainly either joined or crossed the ancient ridgeway (named in the 1219 Perambulation, ‘The Great Way’) which passes by what the Perambulation called the Langeston (i.e. the Caratacus Stone) and Road Castle. But I incline to think that the old Way which passed Mounsey and Brewer’s found its way to the sea at Porlock by a route which still needs to be discovered." (Wybrow 1970 p28-33)

Clovelly Dykes

"Clovelly Dykes [ss311234] is the most impressive set of prehistoric earthworks in Devon: in its final form, it consists of over three kilometres of banks and ditches, defining and defending six enclosures covering eight hectares....Unlike most hillforts it has no natural defence, though sited at a high point (200m) on the coastal plateau. Some small streams rise nearby and there is access by ridgeway from several directions...air photographs reveal that the hillfort is not all of one period. The two concentric enclosures appear to be the earliest and are likely to be where people lived. The entrances are on the east side, where the ends of the outer ditch are intact; other gaps in the defences are recent....the hillfort was greatly enlarged by the building of three strip-like enclosures on the west and north, most probably for stock, and another crescent shaped on the east side...New extra entrances were provided from the NW/NE, in the direction of the springs, screened by a detached line of earthwork with a knobbed terminal. From here there was access to all the strip enclosures, including a narrow 2m wide passageway between the edge of the ditch and the knobbed rampart end. This would provide a vantage place for oversight of the movement of stock, for singling, and even for slaughter. No excavation has taken place at the Dykes; a blue glass bead of Iron Age type was found by a previous farm tenant....The reason for multiple enclosures such as Clovelly Dykes can never be wholly known, but it seems likely they were made to contain and to manage large numbers of livestock, as well as to protect them from wild animals or cattle raiders....Clovelly Dykes probably became a recognised tribal centre and a market place for the district. An export trade is also possible since Strabo, a Greek author writing in the 1st century BC, lists cattle and hides as well as corn, metal and hunting dogs among the goods exported from Britain (Geographica IV, 5.2)" (Fox 1996 p 27-29)

Embury Beacon

"The largest settlements in the area [the South-West] are the cliff castles along the coast, usually set on spurs or promontories and defended by a single or multiple rampart across the neck of the projection. Most are less than 5 acres in area although with precipitous slopes on three sides the area available for settlement was often much less.....Embury Beacon, Hartland, was found upon excavation to enclose several structures, and from the arrangement of the ramparts it can be suggested that its function was similar to that of the multiple-enclosure forts" (Davrill 1990 p 147)

"Embury Beacon [ss216196] was a promontory hillfort on the 150m high cliffs on the west coast, 9 km south of Hartland Point. Erosion has destroyed all but a short length of its two ramparts 40-60m apart. A rescue excavation in 1972-3 recorded the structure of the dump ramparts and a gully, hearths and post holes of a rectilinear building from which some decorated (Glastonbury Style) pottery was recovered, as well as whetstones and shale spindle whorls. These are important as demonstrating this coastal promontory fort is contemporary with those inland." (Fox 1996 p 34)

Wind Hill

"Finally, the most massive earthwork on Exmoor is the great linear fortification at the top of Countisbury Hill [ss740494], about a quarter of a mile west of the village. It defends the ridge between the sea and the gorge of the east Lyn, and the cliffs on either side are adequate protection except at this narrow neck. The height from the bottom of the ditch to the crest of the rampart is as much as thirty feet, and this must have been a truly formidable fortification when first built, no doubt with a massive palisade on top of the rampart. The gateway is a simple gap in the rampart, showing signs of stone revetment which may have extended to part at least of the rampart itself. This type of entrance would indicate a fairly early date, perhaps some time in the third century BC. There is some reason to believe that this fine fortification was restored by the Saxons a thousand years after it was first built and was the scene of a victory over the Danish in 878 AD. If so, some of its impressive character may be the result of that restoration." (Wybrow 1970 p 28-33)

Milber Down

"The earliest forts show a single line of rampart and ditch, either cutting off the neck of a headland (promontory forts) or following the contour of a hilltop. Later on, however, a much more complex type was erected by newcomers in the 1st C BC, one of the largest of which is at Milber near Newton Abbot. This lies not on a hilltop but on a slope, and has four concentric enclosures.....Similar arrangements are found at Wooston and Prestonbury, but the large camp of this type at Clovelly Dykes probably represents a separate landing of the same people by way of the Bristol Channel. Excavation has shown that Milber was occupied for about 100 years, and deserted soon before the Roman conquest." (Sellman 1962 p 11-12.)

"The hillfort on Milber Down [sx883698] is a fine example of a hill-slope fort, constructed on the northern slopes of a 150m high tract of upland between the Teigh estuary and the Aller Brook....Though there are fine views towards Dartmoor to the north, the position is indefensible being 35m below the hilltop, with a further 30m fall internally. The fort consists of three concentric sub-rectangular enclosures: the innermost is 116m by 96m in extent, the second and third are narrow strips 10m to 25m wide, each being defended by a substantial rampart and ditch. In addition there was a large outer enclosure probably for cultivation, bounded by a low bank, now damaged and incomplete. The entrance to the fortifications was on the lower NW side, facing towards the nearest water supply, the Aller Brook. It began as an embanked track 7m wide across the outer enclosure, probably a drove-way for stock to prevent damage to cultivation. The gateways to the inner zones have been destroyed by the modern road. Excavations in 1937-8 showed that the central and second enclosures were occupied, though no house foundations were excavated. The inhabitants used hand-made pottery with curvilinear designs (Glastonbury Ware), characteristic of the local Iron Age after 300 BC. A surprising find of three small bronzes, a bird, a duck and a stag, came from the upper filling of a ditch, buried in the early C1st AD after the fort had been abandoned." (Fox 1996 p 42-3)

(3) Rounds

The simple round (as it would be called in Cornwall), with access across a causeway over the ditch to a rampart-entrance, which is now a mere gap, may reasonably be assumed to be the earliest kind of hill-fort. Most local examples are outside the National Park, but the much eroded enclosure on Kentisbury Down [ss643433], Beacon Castle [ss664640] on the Parracombe-Martinhoe boundary, Roborough Castle (Lynton) [ss731460] and the round on Gallox Hill (Dunster) [ss984427] were probably built at this time. (Grinsell 1970 p77-78) The typical univallate hilltop forts, where the rampart follows the contours of the hill, should be early Iron Age A, such as Cow Castle SE of Simonsbath, Bats Castle south of Dunster, Elsworthy barrows Brendon Hills, Dowsborough on Quantocks and Cannington near Bridgwater. (Grinsell 1970 p 77-78)

Rounds are mostly circular or oval, and enclose from 0.5 to 2 acres. These appear in North and West Devon and the type extends across Cornwall. Excavated sites in Cornwall suggest first sites from C4-3rd BC and they continued to be built long into the Roman period (Pearce 1978 p 84-5)

"It is often said that Britain has an ‘ancient landscape’, in which modern features – settlements, sacred sites, boundaries, and the rest – are built on top of, or near to, precursors that date back centuries or even millennia. Nowhere is this truer than in Cornwall. In 1985...Cornish Place-Names Index (produced by the Institute of Cornish Studies at Exeter University) was marked up on maps, and all medieval settlement place-names entered onto the Sites and Monuments Record (the SMR). ....For some years, also, members of the Cornwall Archaeological Unit have been documenting the number and distribution of ‘rounds’ (enclosed prehistoric farmsteads with a single ditch and bank)...About 650 of these are known already, with many surviving as earthworks, but the number is likely to almost double to 1,000 following the systematic examination of all aerial photographs of the county as part of the English Royal Commission’s National Mapping Programme project. ...become increasingly clear... that areas of land that were enclosed and unenclosed, farmland and heathland, in the medieval period, were used in largely the same way in late prehistory. ......Fogous (stone-built underground chambers) at farms provide similar evidence, such as the one underneath a slurry tank at Pendeen Farm on the Land’s End Peninsula. Fogous are associated with Iron Age settlements, and it is quite likely at Pendeen and other similar sites that an Iron Age settlement developed into a Romano-British ‘courtyard house’, and then later into a medieval farm...... there is evidence of Bronze Age settlement within the late prehistoric farming zone: for example, at Trevisker Round and Penhale Round, where substantial Bronze Age settlement remains were found beneath or next to later settlement. ..... The important point is that the basic farmland/heathland zones appear to stretch back into the 2nd millennium BC, even if we can’t trace continuity of settlement back that far. ....A total of 1,000 abandoned prehistoric enclosures and 2,500 perpetuated prehistoric settlements gives a grand total of at least 3,500 late prehistoric settlements in Cornwall. ..... it would seem that the density of rural settlement in the late Iron Age/Romano-British period was approaching that of medieval Cornwall..... If each was home to about 30 individuals, we have a population of Cornwall in excess of 100,000 people. ..... Devon and parts of Ireland have rounds, as also do parts of Wales (where they are known as raths) ......... I suspect that future archaeological work in these and other parts of Britain’s ‘highland zone’ will find a similar conservatism, and continuity of location, to that which has now been established for Cornwall" (by Nicholas Johnson, County Archaeologist for Cornwall, from www.britarch.ac.uk also in ‘Cornish farms in prehistoric farmyards’ British Archaeology no31 Feb 1998).

"Small enclosures are found as earthworks across most of Devon, but more evidence is being revealed through air photography. Many of these enclosures are rectilinear or square in shape, which is strikingly different from the varied though predominantly ovoid examples from Exmoor, although many are similar in terms of the area they enclose. The dating of these sites is also uncertain at the present time. In Cornwall, similar non-defensive enclosures or rounds, might be a similar phenomenon to Exmoor's hill-slope enclosures. They date from the 4th century BC, with some continuing in use until the 6th and 7th centuries AD. The Cornish rounds are, however, almost always circular, in marked contrast to the Exmoor sites." (Riley & Wilson-North 2001 p 70)

"Hill-slope enclosures form the bulk of settlement evidence for the Iron Age on Exmoor, and yet at present we understand very little about them. We can see them as originating in a gradual shift from unenclosed to enclosed settlements at the end of the Bronze Age, but there is hardly any correlation between hill-slope enclosures and later settlements, and this suggests a lack of continuity....As yet the dating of these sites is problematic. They might mark an enduring tradition of enclosed settlement into the Roman period, or they might be part of a much greater settlement pattern the main component of which is unenclosed settlement. They might be in a sense untypical, the indications of chiefs of minor fiefdoms. What is certain is that they are the single most important area for further research on Exmoor. For without greater insight into their chronology and function, we are unable to answer many of the fundamental questions about Exmoor in the 1st Millennium BC, and perhaps the 1st Millennium AD as well. " (Riley & Wilson-North 2001 p 70)

(4) Hillfort entrances

Newberry has been described as "A typical hill-fort with well marked entrances, ditches and banks with an encircling bank beyond the fort proper. On the plain between the outer and inner bank is an oval mound towards the SE corner" (M G Palmer c1930's, Card index in Standing Stones folder, Ilfracombe Museum) This suggests that it is a multivallate hill-fort, but it is difficult to access and I have not been able to make out the ramparts from a distance.

"Shortly after 300BC there started a much more aggressive series of invasions from northern and western France. These new invaders had had direct contact with Mediterranean cultures, and their chieftains had acquired a taste for luxuries unknown in Britain. It is probable that the earliest hillforts in the SW were built for defence against these invaders, and can thus be dated to the C3rd BC. But not one of the twenty or thirty hillforts in the Exmoor area has yet been excavated, and tentative dating therefore depends on siting and especially upon the architecture of the entrances..... A later type of entrance [rather than a simple gap in a round] is formed by the ends of the ramparts overlapping. An attacker, having crossed the causeway over the ditch, would be forced by the overlap to turn left to reach the gate, thus exposing his unshielded right side to the weapons of the defenders on the rampart. Of this type there are several examples in our area. They include Cunnilear Camp in Loxhore [ss612367] and an unusual linear fortification which protects the end of a spur in Bremridge wood, South Molton. The most sophisticated type of gateway in the Exmoor area is the inturned entrance, in which both ends of the ramparts are turned inwards from the inner end of the causeway over the ditch. There is thus a funnelled approach to the gate, to reach which an attacker would be exposed on both sides to the defenders on the inturned ramparts. In our area there are 3 examples of this comparatively late kind of entrance. The first is at Smythapark in Loxhore [ss636385], where it forms part of a spur-fort which was probably started as a simple round in the early C3rd BC, developing into its final shape some three centuries later. The second example is at Elworthy Barrows, an uncompleted fortress at the east end of the Brendon Hills. The third fort with inturned entrance is of yet another type. Hillsborough at Ilfracombe is a promontory fort or cliffe castle in which a double line of ditch and rampart protect a promontory from attack from the landward side. Here there is an inturned entrance through each line of rampart. Like the other two examples, it is of late date. Smythapark and Hillsborough are both multivallate, that is, they have more than one line of defence. There are several other such hillforts and spur-forts in the Exmoor area, all consisting of an inner enclosure at or near the tip of a spur with one or more cross banks as an extra defence further up the spur. In some cases the inner enclosure is not a complete round, but depends for the defence of part of the perimeter on the steepness of the cliff at the top of which it stands. Examples are Myrtlebury, Lynton [ss743488], Bury castle, Selworthy [ss918472] and Berry Castle, Porlock [ss860449]. An interesting spur-fort where the ‘round’ is complete and there are two defensive cross-banks is on Staddon Hill [ss881377] between Exford and Winsford." (Wybrow 1970 p 28-33)

(5) Date of Devon Hillforts

In North Devon is a small group of hillforts of which Clovelly Dykes is the most striking, an immense series of ramparts covering a greater area than any other hillfort in Devon except Milber. Milber was excavated in 1937 and is from Iron Age B, 100 BC, Clovelly Dykes is of similar age. Iron Age B from Brittany became the Dumnonii (Hoskins 1954 p 34,5)

"The Iron Age produced most, if not all, of the earthwork forts which still crown hilltops and hills in the Devon landscape. Few have yet been properly excavated and the events of this period are at present much less clear than in the downlands to the east. It seems likely that Iron Age invaders came rather later, and the Bronze Age lingered longer, than in Dorset. Most of the hillforts appear to date from the 2nd or 1st century BC, and pottery found in some of them shows a close connection with the Glastonbury Lake Village people. Evidence suggests that the invaders crossed the sea from Brittany, established themselves first near the estuaries of the south-east coast and then penetrated to the borders of Dartmoor. The line of forts north from Buckfastleigh implies a frontier between them and surviving Bronze Age people on the moor." (Sellman 1962 p 11)

From about 300 BC, 3 waves of immigrants came to Britain with La Tène culture, Iron Age B, but only the last wave appeared to have settled in the South-West, probably about 100 BC (Grinsell 1970 p 70)

"It is unfortunate that very few Devon hillforts have been excavated by modern methods or on an adequate scale; we have to rely on the evidence provided from excavations at Hembury in East Devon (1930-5), stoke Hill Camp (1935), Milber Down Camp (1937-8), East Hill Hillfort (1938), Blackbury Castle (1952-4), Woodbury Castle (1971), Embury Beacon (1972-3) and again at Hembury (1980-3)" (Fox 1996 p 6)

"When did the phase of Iron Age civilisation in which hillforts were dominant begin in Devon and how long did it last? It is difficult to say due to the lack of dateable material. Radio-carbon analysis of charcoals (c14 dating) from excavations has been little used in Devon and lacks the precision necessary for this period. The local tribes, known to the Romans as the Dumnonii, did not issue coins, though iron bars of regular weight and sizes were used for exchange in the 1st century BC. A bundle of 12 such currency bars were found near a small hillfort overlooking the river Dart in Holne Chase in 1870 and another find of some 70 discovered recently in the vicinity of Milber Down hillfort. Archaeologists have to rely on potsherds from the few hillfort excavations, principally of the attractive decorated type known as ‘Glastonbury Ware’ (because it was first excavated at the Glastonbury lake village), with incised curvilinear and geometric patterns. Analysis of the clays has shown that such pots were made at various centres in Devon and Cornwall as well as in Somerset, and therefore were traded over a wide area from 300 BC onwards. In Devon, pieces have been found at Blackbury Castle, Cranbrook Castle, Embury Beacon, Hembury and Milber hillforts, whilst at Blackbury castle and Woodbury castle wares of earlier middle Iron Age character indicate that some forts originated in the C4th BC as did Hembury with its characteristic box rampart. When did the Iron Age occupation come to a end? At Milber, the multiple enclosure fort had been abandoned well before the mid 1st century AD when three miniature animal bronzes were buried in the ditch filling. Other forts were probably abandoned before the Roman conquest but these must await identification through further investigation." (Fox 1996 p 15-6)

"The true origins of the Celts lie deep in the mists of prehistory. They were a loosely-knit group of tribes, with connective elements of a common culture and a common language. Traces of these date back to the final stages of the Hallstatt culture (c700-500 BC), which was based in the area around Upper Austria and Bavaria. By the sixth century BC, Greek authors wrote of a people called the keltoni in southern France and, a century later, Herodotus located them in the region around the Danube. In time, their settlements stretched from Turkey and the Balkans right across to western Europe. At the peak of their power, they were strong enough to both sack Rome (386 BC) and Delphi (279 BC). The memory of these victories was soon eclipsed, however, by the rise of the Roman Empire. Here, the lack of cohesion between the various Celtic tribes proved fatal. \one by one, they were overrun or expelled from their territories...The heyday of the ancient Celts coincided with the La Tène era, which flourished in the last centuries before Christ (c480-50 BC)" (Zaczek 1996 p 6)

The hill-slope enclosures in north Devon may be considerably older than usually thought. The recent excavations at Holworthy enclosure found evidence of use in the Bronze Age and evidence that the site was abandoned even before the beginning of the Iron Age (see section 2 above)

(6) Ridgeways

"Also important were the ancient ridgeways, running along watersheds and avoiding the forest and swamps of the valleys. These had been in use since early Bronze Age times, and some remain as roads today: one forms a long stretch of the county border on Exmoor.....Many of the [Iron Age] forts were built on or near them. In the wet climate of this period the highest ground was too damp for settlement, and the valleys had not yet been opened up by clearance and drainage. Most of the IA population seems therefore to have lived somewhere near the 500’ contour." (Sellman 1962 p 13)

"The Phoenicians built it [the old road to Barnstaple] when they came here to trade, they would take back Cornish tin to mix with their copper...the road is said to be 4,000 years old" (Wilson 1976 p 71)

"The lines of prehistoric routes are largely speculative but various physical features do provide useful clues. The presence of barrows has already been mentioned. The boundaries of parishes and counties were laid down between the C8th and C10th and tracks were often used to mark the boundaries. Thus a contemporary road or track contemporary with a parish or county boundary indicates that the track or road existed before these centuries......’harepath’ means ‘highway’ or ‘army way’, ‘anstey’ means a track wide enough only for one person and ‘sal’ or ‘salt’ derives from the production of salt. Bronze or Iron Age settlements can be expected to have tracks leading to them." (Hawkins 1988 p 10)

(7) Dumnonii & Trade

The Dumnonii got their name from Celtic root Dumno- or Dubno- which as a noun means ‘world’ or ‘land’. The tribal name therefore meant ‘the people of the land’ (TDA 79 1947p16). Another theory that Dumnonia meant deep valleys rests upon the modern welsh form of Devon, Dyfnaint (Hoskins 1954 p 9)

"The tribe which occupied greater Exmoor during this phase from about 100BC onwards, if not earlier, was known as the Dumnonii, a word which has been claimed to mean ‘people of the land’. These are most probably the people of Devon and Cornwall described by Solinus (writing in the C3rd AD but quoting from a writer from 3 centuries earlier) as refusing to accept coin and performing their business transactions by barter. (Grinsell 1970 p73) no coins attributable to the Dumnonii have yet been found (Grinsell 1970 p 74)

"Unlike their Belgic counterparts further along the coast, the Dumnonii seem to have been a loosely organised tribal confederacy composed of a number of loosley knit cheifdomships, lacking political cohesion and a recognised leading dynasty, for unlike their neighbours, the Durotriges in Dorset and the Dobunni in Gloucester, they issued no coins of their own. Thomas [1966 p82-3] has shown that even in the 1st century AD, the Dumnonii seem to have been comparatively economically backward and culturally isolated." (Whitehead 1992 p 9)

"Not all the Iron Age people in Devon were farmers: a few were traders. At Mount Batten on the Eastern side of Plymouth Sound, there was an important settlement of traders perhaps 200 years before the Roman conquest. Much pottery has been found here, a complete cemetery and many coins, which suggest trading with Gaul....There was probably a considerable trade across the channel and perhaps as far away as the Mediterranean. We do not know what these early Devonshire traders exported, but it was certainly not tin....It is possible that such trade as there was....was mainly in cattle, hides and leather. At the earthworks at Holne Chase a number of iron currency bars were discovered many years ago. Iron bars at this time were a form of money...This discovery...suggests some kind of important trade. " (Hoskins 1959 p 18)

There was another influx of Celts around 500 BC. The La Tène tribes (named after the area in Switzerland where a significant number of remains have been found) came for the tin. The Greek geographer Pytheas of Massilia sailed around Spain and up to Britain just before 300 BC where he explored. His account is lost, but is referred to by later writers. Here we have the first real descriptions of tin working and the mode of export, which described exactly St Michael's Mount, which becomes an island at high water. This is the Isle of Ictis or Iktis, from which the tin trade to the early Roman Empire was started. Miners would take their tin, beaten into the shape of ox-hides, in wagons over to Ictis at low tide. The merchants would come to Ictis, buy tin from the local miners and ship it to Northern Gaul (Colby, John & Sandy, Cornish Celts website 2001 [no longer available]

(8) Recent finds

A Roman-British site in the north of Brayford Parish has been known for several years and Brayvale site near the village centre showed signs of slag from smelts and when excavated slag and Roman pottery shards were found with possible Iron Age pottery beneath. A coin found higher up is from the mid 3rd Century (Jim Knight, North Devon Archaeological Society Autumn/winter 2001 pp 8-10)

"The earliest dated smelting site on Exmoor lies at Sherracombe Ford, deep in the Upper Bray valley. The remains of two large slag heaps and a range of platforms terraced into the hillside survive as earthworks on a steep slope in a pasture field. The three large double platforms are probably smelting platforms, with furnaces and bellows, perhaps within shelters. ...radiocarbon dates have now placed the two large slag heaps in the Late Iron Age - Romano-British period (Juleff 2000)....The proximity of several of Exmoor's hillforts to significant iron ore deposits should be noted, although there remains much work to be done on the chronology of both the hillforts and the iron-working sites" (Riley & Wilson-North 2001 p 80)

I visited the Brayford site in 2002 and saw last year’s excavation in a bank beside the road at Bray Vale, and saw this year’s excavation behind a barn, slightly uphill of the other site, thought to be a preparation area. Two blackened pits were found here, thought to be Iron Age since they were sealed by Roman debris including Simian ware and black pottery from Dorset.

"An intensive dig to uncover the secrets of Roman Exmoor is drawing to a close at Brayford...The team has uncovered the remains of several furnaces used to smelt iron and even an intact tiled smithy floor encrusted with generations of waste iron, known as 'hammer scale'. There are two huge dumps on the site, each containing many thousands of tonnes of slag - the waste product from iron smelting - and it is estimated that hundreds of tonnes of metal were produced. Pottery uncovered has dated the site's use from the 2nd to 4th century AD, but there is evidence it was used much earlier during the Iron Age. For a long time historians tended to assume there was little or no Roman activity in north Devon and the rest of the south-west, but this year's dig and previous ones at Brayford suggest otherwise" (North Devon Journal Sept. 17th 2003)